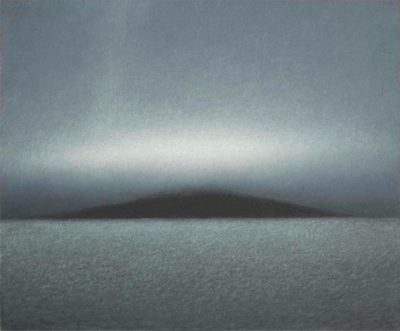

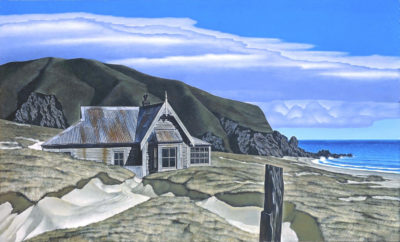

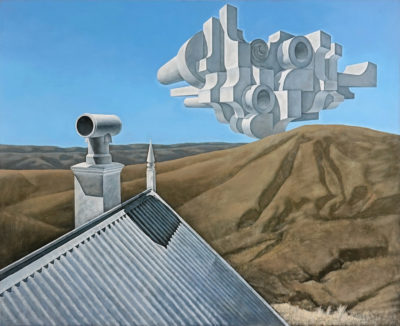

Central to Wong’s practice is the idea of the landscape not as a physical place but as a psychological stage. While his terrains may evoke New Zealand features such as open skies and rolling hills recognisably, they are not rooted in specific geography nor intended as expressions of local identity. Instead, these dreamlike vistas provide the setting for carefully structured compositions, where human presence is conspicuously absent. Deserted buildings and geometrical structures emerge as stand-ins for memory, introspection, and inner disquiet.

Wong’s early works often began as spontaneous line drawings or architectural doodles made during his night shifts as a copyholder at The Dominion newspaper. These sketches evolved into formalised compositions frequently characterised by exaggerated perspectives, stark contrasts, and suspended or unexplained objects. The result is a pictorial language that evokes the eerie silence of a stage before the performance begins: tension without resolution, presence without narrative. This atmosphere of stillness and disconnection is not accidental. Wong’s practice emerged in parallel with periods of depression and anxiety, and many of his images can be read as a visual autobiography of those psychological states. His paintings do not depict specific memories or events but embody the emotional and existential conditions that shape the self. The haunting stillness that permeates these compositions speaks to a deeper metaphysical enquiry: what it means to exist, observe, and be apart yet within.

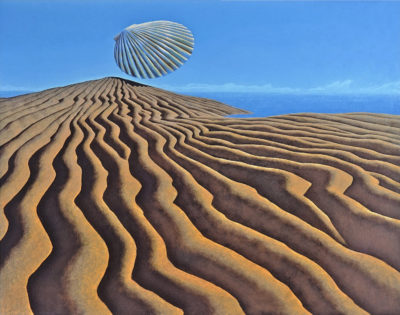

The absence of figures heightens the emotional charge of Wong’s works. Structures appear either derelict or displaced, divorced from their environment and each other. These enigmatic forms, often rendered with architectural clarity but surreal juxtapositions, challenge the viewer’s sense of spatial logic. The floating elements, such as roofless buildings, blocks of shadow, and airborne forms, introduce an unsettling ambiguity. Their unanchored presence implies unseen forces at play and invites reflection on the unknown or unknowable aspects of human experience. Despite their spareness, Wong’s paintings are painstakingly constructed. He often spent years on a single canvas, building up countless layers of acrylic to achieve a luminous, almost jewel-like surface. This slow and deliberate process aligns with his deeper interest in the meditative nature of the static image, a theme that became increasingly central to his work.

Brent Wong was born in 1945 in Ōtaki, New Zealand, and raised in Wellington. His family home on Vivian Street overlooked a dense patchwork of rooftops and inner-city architecture, an outlook that profoundly influenced his early visual vocabulary. Wong experienced reading difficulties as a child, denying him the escapism enjoyed by most young children and so he began drawing as a means of communication, fulfilment, and self-expression. His unconventional approach made school life difficult, and he left early. In 1963, he enrolled briefly at Wellington Polytechnic’s School of Fine Arts but soon left formal study to pursue an independent path as a self-taught artist. Initially focused on drawing, Wong experimented with watercolours and oils before settling on acrylics, drawn by the medium’s fast drying time and ability to support multiple-layered revisions. Many of his earliest structured compositions evolved from automatic drawings or sketches made as a therapeutic activity during bouts of depression. These formed the foundations for an increasingly introspective and symbolically rich painting practice.

Though his art drew critical attention early on, Wong’s first solo exhibition was held in 1969; he maintained a private, often reclusive approach to his work. He has never painted from life or photographs; his landscapes and architectural elements are constructed from memory and imagination, carefully planned and executed over extended periods. This internalisation of subject matter contributes to his oeuvre’s metaphysical and timeless quality.

In the 2000s, Wong shifted his creative focus from painting to music composition, exploring new dimensions of meditative and symbolic expression through sound. His visual works, however, remain widely collected and held in major public institutions, including Te Papa Tongarewa, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, and the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū.

Wong’s paintings continue to resonate for their quiet power, refined technique, and singular vision, offering viewers profound spaces for contemplation and introspection.